A friend and colleague asked me to take a look at a new graphic novel, Indeh by Ethan Hawke and Greg Ruth. She is considering it as a text for her secondary history and social studies education class. At first glance it looked interesting, so I agreed to read it with a more critical eye.

The Book

Ethan Hawke, yes … Ethan Hawke the actor from Gattaca, Snow Falling On Cedars, and Boyhood … has been fascinated with Indians of the old west since he was a child. As an adult his fascination continued and he watched movies like Smoke Signals and read books by Sherman Alexie to get an authentic view of the Native American experience. According to Hawke’s author note Indeh was originally a screenplay that he had no luck getting it to the screen. Instead, Hawke connected with Greg Ruth and created a graphic novel based on Hawke’s study of history.

The Issue of Representation

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center found in their survey of 2015 children’s books there are painfully few representations of American Indians in books written for children. In addition to the sheer lack of books, the actual representations are warped most of the time.

My “Knowledge”

My scholarship focuses on representation of marginalized people in graphic novels. That is a big group of people and includes many communities I am not a part of, and have little knowledge about. When I read a graphic novel that centers a marginalized community I am not a part of I have to do some extra work and ask questions of myself as a reader. I usually begin by making a list of what I “know” about the community, and this “knowledge” includes my own biased views, stereotypes and family lore. For this books I wrote a list about Apaches;

- Apache live in the southwest desert.

- They live on both sides of the boarder.

- According to my grandfather when the Anasazi abandoned their lands half when north and became Pueblo, Apache and Navajo indians. The other half went south and became Cora (my family) and Huichol.

- My tio Jesus (HEY-sus) – who was actually my great uncle on my grandfathers side – was called el Apache or el indio by our family.

- Apaches were great fighters and basically kicked our (Mexican) butts in 2 wars. First, in 1821, just after Mexico gained independence, and then again around 1880.

- The 1880 war where Geronimo and Chato rose up and kicked Mexican butts.

- Mexico has never had a great army.

- The first Mexican battles against Chato and his Apache warriors – and I am never sure who the players were or what side my family members were on – took place in Chihuahua where my tia Theresa’s family originated.

- Apaches are awesome fighters, can live on nothing but dust, and never forgive their enemy.

- All of the stories I heard are about Apache men – never women.

- Although I suspect there are different bands of Apache, I have no idea what those bands are or where they are located.

Reading the Words and Images

The inside cover is a two page black and white spread depicting a level of violence I would usually just skip over. Men with hand guns, rifles, bows and arrows killing and being killed. I spent some time on this image and came to realize that the White men – as signaled by their clothes and equipment – were dead or being killed whereas the Apache were the ones doing the killing. In one section an Apache seems to be turning from killing one White man who lays on the ground towards another who is struggling with two arrows in his back. The Apache has no shirt on, and there is blood spilling off the knife in his hand.

There is an extremely complimentary foreword written by Douglas Miles, owner of Apache Skateboards. Miles is a member of the Apache nation.

The beginning of the books is difficult to place in time. It seems to jump from “present” to “past” but there is no way for me, as a reader, to orient myself to the time period.

The book opens with Cochise telling two boys, Naiches (his son) and Goyahla, a creation story while standing in a stream. This fades into a first person narrative by one of the boys who states, “Many of our people had lost much in the massacre … … but I had lost all”. This line is set beside the image of a person’s forehead and one open eye, their long, dark hair flowing across the panel from right to left, with blots of something that could be ink or blood. (p.9, pn. 3).

The next page has a banner “Seventeen Years Later – Mexico” and a single panel makes up the entire page. A man sits close by a woman who appears dead and bloody. The story in the text is that of a man who had to bring 100 ponies to win permission to marry. The panels alternate between a light grey past filled with intimate closeup of the man and woman and his collecting the horses, and what seems to be the present violent death of a woman. There is no clear perpetrator. There is no other person aside from the man who seems to be the narrator. I was not sure if he had killed his wife or if his wife was killed by unseen forces.

As I read further, it became clear there was a mass killing and this man, Goyahla, had survived but his wife and daughter were killed. He sets a funeral pyre alight (p. 20) but on the next page it is not on fire and a hawk or eagle lands on the pyre and tell Goyahla that he will be impervious to guns (p. 22-24). He asks permission to lead a war party against the Mexicans who are, according to the text, responsible for the deaths of his family. For the next few pages Goyahla and Cochise raise an army from among the Bands of the Apache nation.

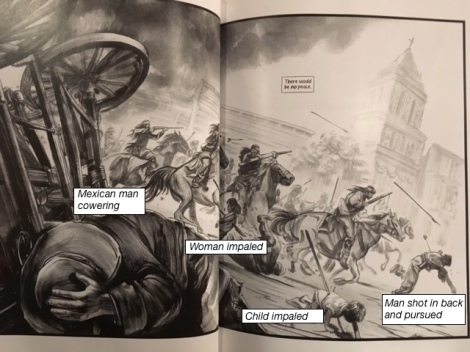

The next two-page spread (p. 34-35) is another bloody, violent scene full of smoke, running horses, and death. What struck me about this and many other pages within this book was the way the violence is portrayed, and by whom and upon whom the violence is being inflicted.

What I want readers to see in this example is that the Apache are on the move, shooting and killing unarmed men, women, and children. Thus far they are the ONLY violent actors shown.

On page 39 Goyahla is shown in the act of scalping someone. On page 41 he rams a knife through a mans chin and into his skull. On page 42 and 43 Mexicans are seen as bleeding victims with arrows and spears protruding from their bodies. On the second panel of page 43 a dead baby is seen floating down a river. The image is tied in with the sequence of the Apache killing unarmed Mexicans.

The book continues in this manner. Neither White Americans nor Mexicans are seen as the actual perpetrators of any level of violence. The images in the book are almost always of the aftermath of massacres or killings by the army on the Apaches. The military are responsible for the hanging deaths of a groups of Apache on page 94-95, but the immediacy of the act is not shown, only the aftermath. Again and again White soldiers are depicted threatening violence and the American government makes and breaks promises and treaties, but the direct image of Whites perpetrating violence on Apache bodies is not seen, over and over again.

– On page 136 an army officer shoots a horse in the head to use it as a road block. On page 137 a bullet comes from outside the panel, from an unseen shooter, and goes through an Apache’s head.

– Pages 146-155 show the killing of Magas Coloradas, an Apache leader who was shot and beheaded by US army soldiers. Coloradas’ death is not shown. Instead, the panel (p. 151, pn. 4) shows Lieutenant Gatewood’s reaction to hearing the shot outside his tent.

– There are Apache heads on pikes (p. 163) but no image of them being beheaded.

– During a series illustrating a battle at Skeleton Cave in Arizona (p. 174, pn 1-3) the US soldiers have rifles in panel 1, a bearded man says “Buck, see that fella up front?”. Panel 2 shows an Apache with a rifle being shot several times. Panel 3 shows 4 other Apache, one with a rifle, being shot. But, again, the perpetrators of the shooting are not depicted.

This separation of violence and perpetrator is ONLY afforded to the US and Mexican soldiers and not to the Apache. The Apache are seen, within panels, as the direct perpetrators of violence against friends and enemies alike.

This graphic novel is a problematic text. In my scant review of the literature under “further reading” (p. 231) and my research into the specific battles shown, this book shows an extremely biased history as told by White americans. The fact that ONLY the Apache are seen as direct perpetrators of violence against women, children, unarmed and armed men is a huge concern for me.

To answer my colleague who asked if Indeh is a good graphic novel to use in her secondary history and social studies education classes, I have to say no. It is yet another example of a distorted, overtly violent and damaging portrait of an angry and brutal Apache Nation. Don’t bother buying it. The authors don’t need to be rewarded.

EDIT – please see Debbie Reese’s excellent review which focuses on the historical accuracy of the book, American Indians in Children’s Literature.

Such a thoughtful review and analysis! I have been wrestling with how to teach my pre-service teachers to recognize and evaluate problematic texts, and your post has given me some ideas. I will definitely be sharing your approach with them next semester, so thank you for taking the time to share this.

Laura–here’s my review: https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2016/12/not-recommended-indeh-story-of-apache.html

Elisabeth–to do the work you’re thinking about doing, I use LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE and various sources that allow college students to see the inaccuracies in LHOP.

Thanks! I’ll add this to the body of the post too.

Thank you so much for your work here. I appreciate your reflection on this book in part because you have articulated the issues, but you have also provided a model for how to unpack books like this.

Thank you! I’ve been trying to articulate HOW TO engage in texts that are not within my communities.

Very good to read your thoughts about this graphic novel.