There are plenty of people telling me I am too harsh on children’s books. I’m too quick to call out the overwhelming Whiteness of authors, illustrators, editors, and critics. I get pushback for directing criticism to our children’s literature organizations, literacy associations, critics and bloggers.

There are times when someone takes me to task and I wonder – have I gone too far? Am I part of the PC internet-Twitter-mob? (Is that even a thing?) Am I looking for racism, sexism, ablism, and homophobia where it isn’t?

Then I look to other critics who are, by in large, NOT straight, White, able or male and I see the same reactions, the echoes, the same plea for respect.

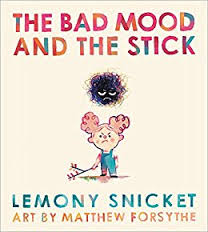

Recently Edi Campbell tweeted out a book cover and asked a small number of critics (including me) if we saw “the problem”.

“the problem”.

I’ll admit I didn’t see what the issue was at first. I barely looked at the girl, noticed the book was written by Lemony Snicket (AKA Daniel Handler) and thought …. “What am I not seeing here? God, is there another watermelon joke?” I trusted my colleagues and I knew that if I wasn’t seeing the problem it did not mean there was not a problem. It meant I was not seeing the problem.

So, I asked.

And, the answers were awful.

First, Sarah HANNAH Gomez (@shgmclicious) tweeted out the book cover, accompanied by the racist image of a golliwog. Although usually found in the UK, the golliwog is yet another blackface image we could do without.

Then, Allie Jane Bruce provided another kind of image.  There it was. The awful truths. That “mood” was a call-back to a racist visual trope aimed right at Black and African American kids who would see it and feel it, even if I did not Once I saw it I could not unsee it. Read Edi Campbell’s blog post about the book here CrazyQuilts blog.

There it was. The awful truths. That “mood” was a call-back to a racist visual trope aimed right at Black and African American kids who would see it and feel it, even if I did not Once I saw it I could not unsee it. Read Edi Campbell’s blog post about the book here CrazyQuilts blog.

We have to decide, as a community of book lovers … do picturebooks matter? Do they help kids see the world? Do they help kids build themselves? If reading and books matter than we have to come to the realization that images within books matter, too. We cannot believe that books are important but that representation isn’t. We, as a community of educators, cannot have it both ways.

It matters that this book confirms the age old visual trope of black = bad, and curly = unruly and must be tamed! (see the stick). If picturebooks matter than the messages contained within the words and images matter even if we, as adults, do not initially see those messages.

After emailing and tweeting the author and the publisher for a few days, there was a response – an actual apology. Not a “sorry YOU took offense” but an actual “oops” and promise to do better.

Books matter. Those of us who’s identity was built in part by the books we read know this to be true. Books save lives, they open doors, they allow us to escape into worlds and possibilities beyond what we see. But, the flip side of this is that books can damage and degrade readers who see themselves represented as the problem, the issue to be solved, the condition to be cured.

That is what many critics, book bloggers, and awards committees do not want to admit. The lists and honors matter to teachers and parents because they rely on experts. But, who is the expert on non-White, non-heterosexual, disabled representations?

Again, I did not see the problem even when it was, literally, staring me in the face.

The Eisner award nominations came out about a week ago and Raina Telgemeier’s Ghosts was on the list. She appropriated Latinx culture, and completely erased Native American history in her graphic novel (link to my critique, link to Debbie Reese’s critique). I’m not surprised but I am disappointed by the nomination.

White authors using culture and identities as cheap plot devices and lazy tropes – including books like Telgemeier’s Ghosts – isn’t new. The overwhelming, overrepresentation of White, straight, able males in children’s books isn’t new.

What is new is our voices on social media. We will not be silenced by a call for niceness. Instead, we will raise our voices to be heard above the din of fragility. We echo each other. We seek out allies who recognize the beauty of diversity, and the strength of hearing stories in told in #ownvoices, like Gene Yang’s Reading Without Walls Challenge. If all your book lists, including that stack of books you have ready for summer reading, feature people who look and sound like you, make an effort to read beyond yourself.

Start with 2017 We’re The People book list.

Read blogs like Latinxs in Kidlit, The Brown Bookshelf, Disability in Kid Lit, CrazyQuilt, The Dark Fantastic, and American Indians in Children’s Literature.

This post reminded me of a review I did last year of a book called A Country Far Away. I looked for a long time and could only find positive reviews and even examples of teachers using this in their classrooms. There are so many things I miss that #ownvoices reviewers catch, and I think we’re starting to see the problem with having a mostly straight, white, cis, able-bodied publishing industry thanks to these critical reviews.

If people are looking for an alternative, Ahn’s Anger is a diverse (but not #ownvoices) picture book about managing anger that my family has enjoyed.

Funny you mention A Country Far Away – it was a bete noir for a critique group I was involved with over 20 years ago… sad to see it’s still in existence.

I wonder why the illustrator wasn’t also contacted rather than “emailing and tweeting the author and the publisher”? Seems like a strange exclusion, considering that was the source of the problematic content.

Because – in this case – the author (Daniel Handler) and the publisher (little brown and co) were the ones with the ability to change the book. In this case, as with many picturebooks, the illustrator has little editorial power.

Thanks for the quick reply and explanation!!! I’m really impressed that you knew that they were the ones who had the power. I have so much to learn from those of you who have been in the book world for a long time. I still wonder about the illustrator’s role in this… editorial power or not, Matthew Forsythe was the source of that image.